Fall of Enugu

| Fall of Enugu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Nigerian Civil War | |||||||

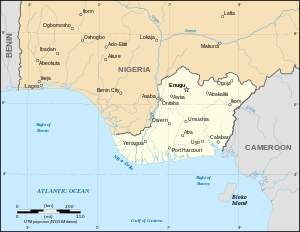

Map showing the claimed territory of Biafra in June 1967 with key locations including Enugu | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Theophilus Danjuma |

Odumegwu Ojukwu Alexander Madiebo | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7 battalions |

1 brigade c. 10,000 armed civilians | ||||||

The fall of Enugu was a military conflict between Nigerian and Biafran forces in September and October 1967 during the Nigerian Civil War which centered around Enugu, the capital of the secessionist Republic of Biafra. Nigerian federal forces had made Enugu's capture a priority shortly after war broke out, but their advance stalled at Nsukka. Biafran president and leader Odumegwu Ojukwu, attempted to distract the Nigerian Army by initiating an invasion of Nigeria's Mid-Western Region in August, but the offensive was brought to a halt. Lieutenant Colonel Theophilus Danjuma took charge of the Nigerian forces at the Nsukka front and prepared to advance on Enugu with seven battalions of the 1st Division. Enugu was garrisoned by one brigade led by Colonel Alexander Madiebo and poorly armed civilians called into service. Danjuma decided to launch an offensive with his forces spread over a broad front to make it more difficult for the Biafrans to block them along major roads as had happened up to that point.

The Nigerians began their advance from Nsukka on 12 September. Biafran forces attempted to slow them by counter-attacking and felling trees, but within a few weeks the Nigerian forces had reached Milliken Hill and concentrated their forces. Federal artillery began bombarding Enugu on 26 September, while the Nigerian Air Force conducted raids. Ojukwu pledged to not abandon the city, but the Biafrans began evacuating on 3 October. The Nigerian forces attacked the following day, occupying the city with minimal resistance while Ojukwu narrowly escaped. Many Nigerians hoped that Enugu's capture would convince the Igbos' traditional elite to end their support for secession. While its loss did destabilize the Biafran war effort, Ojukwu relocated his government to Umuahia, and its propaganda concealed the loss of the city, meaning most Biafrans were not aware of Enugu's capture until the end of the war.

Background

[edit]In the late 1960s ethnic tensions rose dramatically in Nigeria. Many Igbo people of eastern Nigeria feared domination and discrimination from the country's other ethnic groups. In September 1966 soldiers of the Nigerian Armed Forces massacred easterners residing in the northern portion of the country, triggering the flight of thousands more to the eastern city of Enugu. On 30 May 1967, Nigeria's Eastern Region declared that it was seceding from the country to become the independent state of Biafra. Enugu was made Biafra's capital, and the state was led by the former Eastern Region Military Governor, Lieutenant Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu.[1] The Nigerian government planned to suppress the secession in a four-phase operation that would last one month. Their first major goal was to secure Enugu and Nsukka.[2] On 6 July Nigerian federal troops launched their offensive to recapture Biafra, initiating the Nigerian Civil War. Federal officials initially declared that their forces would seize Enugu "in 48 hours", but the conflict soon developed into a stalemate, with heavy fighting taking place near Nsukka.[1] Amunition shortages also hampered the Nigerian offensive.[3]

At the start of the war, Enugu was home to almost 140,000 residents,[4] mostly Christian Igbos. Once conflict broke out, they started leaving the city in search of refuge deeper in Biafran territory.[5] Foreign nationals were advised by their own governments to leave Biafra, and by late July only about 50—most of them journalists, arms dealers, diplomats, and traders—remained in Enugu.[1] In an attempt to distract federal attention away from Enugu, Ojukwu ordered an invasion of Nigeria's Mid-Western Region. Biafran troops began their offensive in August and made steady progress, capturing Benin City and almost coming within 100 miles of Lagos before being halted at Ore.[6] Federal forces were reinforced by redeploying troops from the Nsukka front, delaying progress on the attempt to capture Enugu.[7] The Nigerian 2nd Infantry Division led a counteroffensive in the Mid-Western Region and by late September had recaptured Benin City.[8] Meanwhile, the commander-in-chief of the Nigerian Army, General Yakubu Gowon, ordered Major Theophilus Danjuma to assume the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel and relieve Sule Apollo of command of the detachment of 1st Division troops at the Nsukka front. Danjuma spent the following weeks securing his supply and communication lines.[9]

The Biafran 53 Brigade under Colonel Alexander Madiebo, the newly appointed head of the Biafran Army, was tasked with defending Enugu, but the unit had been exhausted by previous engagements and was unable to call upon reinforcements. In an attempt to bolster the city's defence, Ojukwu ordered all able-bodied men mobilised. Approximately 10,000 arrived in the capital. Aside from a handful of dane guns in their possession, the men were unarmed and the Biafran administration struggled to feed them. According to Madiebo, Ojukwu intended to equip them with machetes and move them through Eke from where they would swarm federal troops at Abor. Madiebo doubted the plan's feasibility.[10]

In contrast to the motley defenders of Biafra's capital, the troops tasked with attacking Enugu were from the 1st Division, which was the most experienced force in the Nigerian Army. It included large numbers of World War II veterans.[11] Overall, Danjuma was given charge of six full battalions and 2,000 troops as reinforcements, which he organised into one additional battalion with the remaining 1,000 troops held in reserve.[12] Feeling that the divisional headquarters at Makurdi was too distant and out of touch with the situation, Danjuma ignored orders dispatched from there and instead gathered his officers at his brigade headquarters to design an offensive. He devised a plan whereby Nigerian forces would advance along a broad front, thus making it more difficult for the Biafrans to block them along major roads as had happened up to that point.[13] He then went to Makurdi to inform divisional commander General Mohammed Shuwa of the plan.[14]

Nigerian offensive

[edit]

Nigerian forces in the Nsukka area began advancing in earnest towards Enugu on 12 September.[15][12] Armed mostly with small arms and some anti-tank weapons, the troops kept in close contact with each other so as to keep the line of advance even.[14] Biafran forces counter-attacked,[15] and Nigerian troops on the main road were subjected to significant amounts of fire, but the rebels guarding the secondary roads were surprised and quickly retreated.[14] Biafran troops dug craters and chopped down trees to block roads as they pulled back, slowing the offensive.[16] The federal forces progressed from Opi Junction to Milliken Hill within a few weeks.[17] Federal artillery in Ukana began bombarding Enugu on 26 September.[18][16] The Nigerian Air Force also raided the city, temporarily forcing Biafran radio offline.[19] Having obtained armoured cars by the time he reached Milliken Hill, Danjuma had his forces link up before moving ahead on a narrower front to concentrate their strength.[20] News of the 2nd Division's success at Benin City and Ojukwu's decision to execute some of his top officers boosted federal morale.[16]

Just after midnight on 1 October, Ojukwu delivered a speech over radio pledging not to abandon Enugu.[21] On 3 October, the Biafrans began evacuating their capital.[22] Danjuma employed a plan of attack for the city he had originally devised as a hypothetical scenario during a promotion examination some years prior.[23] On 4 October, federal air and ground forces assaulted the city.[19] Ojukwu was asleep in the Biafran State House when the federal troops attacked, and awoke to the sound of gunfire and mortar explosions to find his guards and aides gone and the building surrounded by federal forces. Disguising himself as a servant, he was able to walk past the cordon without incident and escape.[24] Minimal fighting took place within Enugu[23] and the Nigerian 1st Division successfully occupied the city.[25]

Aftermath

[edit]Situation in Enugu

[edit]Danjuma described the fall of Enugu as "an anticlimax".[5] His troops garrisoned the city in the immediate aftermath of the battle,[5] while Ukpabi Asika, an Igbo professor at Ibadan University, was appointed to lead the civil administration in the locale and surrounding areas held by federal forces.[26] The Nigerians seized one Biafran Douglas A-26 Invader.[27] Danjuma operated out of Enugu for most of the remainder of the war.[20] After its capture, buildings in Enugu were ransacked by looters and federal troops, including the Presidential Hotel and the United States Consulate.[4][5] The vast majority of the population fled, and only approximately 500 civilians remained, most too ill, old, or young to leave. Nigerian federal officials unsuccessfully appealed for residents to return to the area.[5] Over a year after the battle, the city remained mostly deserted, and most of the few hundred civilians in Enugu were being sheltered and cared for by Catholic missions. The International Red Cross established a station in the locale, and used it to direct the distribution of relief supplies to the surrounding area.[4] As late as 1978, signs of damage from the battle remained in the city.[28] Nigerian writer Chukwuemeka Ike later portrayed the fall of Enugu in his novel, Sunset at Dawn.[29]

Course of the war

[edit]Many Nigerians hoped that Enugu's capture would convince the Igbos' traditional elite to end their support for secession, even if Ojukwu did not follow them.[30] The 1st Division halted its operations at Enugu to rest and resupply and let Ojukwu consider abandoning the rebellion.[31] This did not occur; Ojukwu relocated his government without difficulty to Umuahia, a city positioned deep within traditional Igbo territory,[30] where it affirmed its intention to continue resisting.[32] The 1st Division remained halted in Enugu for six months. Nigerian military officer Olusegun Obasanjo stated in his memoirs that if the unit had not delayed it could have pursued and destroyed the Biafran forces, thus ending the war sooner.[16] Other federal forces pressed on with their offensive throughout October, securing Asaba and Calabar, further encircling Biafra.[33] Umuahia was not taken by Nigerian government troops until 22 April 1969.[34]

The fall of Enugu led to the loss of significant stocks of equipment and supplies for the Biafrans.[35] It also contributed to a brief destabilisation of their propaganda efforts, as the forced relocation of personnel left the Ministry of Information disorganised and the federal force's success undermined previous Biafran assertions that the Nigerian state could not withstand a protracted war.[36] On 23 October 1967 the Biafran official radio declared in a broadcast that Ojukwu promised to continue resisting the federal government, and that he attributed military reversals to subversive actions.[5] Biafran radio moved its broadcasting station several times throughout the war, but would often pretend that it was still headquartered in Enugu to maintain morale. As a result, many Biafrans were not aware of the city's capture until the end of the war.[37]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Garrison, Lloyd (29 July 1967). "Eastern Nigerian Rebels Weather Their First Test". The New York Times. pp. A1, A3.

- ^ Gould 2012, p. 59.

- ^ Gould 2012, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Emerson, Gloria (13 October 1968). "Enugu, Nigeria: Silence in War's Wake". The New York Times. pp. A1, A3.

- ^ a b c d e f "Nigerian Civil War Makes Enugu a Ghost Town". The New York Times. 24 October 1967. p. A20.

- ^ Moses & Heerten 2018, pp. 412–413.

- ^ Gould 2012, p. 65.

- ^ Moses & Heerten 2018, p. 413.

- ^ Barrett 1979, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Momoh 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Jowett 2016, pp. 6, 9–10.

- ^ a b Obasanjo 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Barrett 1979, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c Barrett 1979, p. 65.

- ^ a b Venter 2016, p. 208.

- ^ a b c d Obasanjo 1999, p. 20.

- ^ Barrett 1979, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Moses & Heerten 2018, p. 160.

- ^ a b Nigeria's War 1970, p. 9.

- ^ a b Barrett 1979, p. 66.

- ^ Meisler, Stanley (1 October 1967). "Nigerian Troops Open Siege of Biafra Capital". The Los Angeles Times. p. F2.

- ^ Stremlau 2015, p. 97.

- ^ a b De St. Jorre 1972, p. 173.

- ^ Baxter 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Jowett 2016, p. 6.

- ^ Gould 2012, p. 75.

- ^ Venter 2016, p. 155.

- ^ Lamb, David (18 November 1978). "Ibos Rebuild: Time Fades the Bitterness of Biafra War". Los Angeles Times. pp. A1, A11.

- ^ Okafor 2008, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Stremlau 2015, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Venter 2016, p. 209.

- ^ De St. Jorre 1972, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Stremlau 2015, p. 98.

- ^ Stremlau 2015, p. 218.

- ^ De St. Jorre 1972, p. 174.

- ^ Stremlau 2015, p. 111.

- ^ Omaka 2018, p. 574.

Works cited

[edit]- Barrett, Lindsay (1979). Danjuma : The Making of a General. Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers. OCLC 6638490.

- Baxter, Peter (2015). Biafra: The Nigerian Civil War 1967-1970. Helion and Company. ISBN 9781910777473.

- De St. Jorre, John (1972). The Brother's War : Biafra and Nigeria. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 9780395139349.

- Okafor, Clement A. (2008). "Chukwuemeka Ike's Sunset at Dawn". African Literature Today (26): 33–48. ISBN 9780852555712. ISSN 0065-4000.

- Gould, Michael (2012). Struggle for Modern Nigeria : The Biafran War, 1967-1970. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9780857730954.

- Jowett, Philip S. (2016). The Nigerian-Biafran War 1967–70. Modern African Wars. Vol. 5. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472816092.

- Momoh, H. B. (2000). The Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970: history and reminiscences. Sam Bookman Publishers. ISBN 9789782165961.

- Moses, A. Dirk; Heerten, Lasse, eds. (2018). Postcolonial conflict and the question of genocide : the Nigeria-Biafra War, 1967-1970. Florence: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-34758-7.

- Nigeria's War (July 6, 1967-January 12, 1970): A Diary of Events. Lagos: Daily Times Limited. 1970. OCLC 297706.

- Obasanjo, Olusegun (1999). My Command (reprint ed.). Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. ISBN 9789966250216. OCLC 42948795.

- Omaka, Arua Oko (2018). "Conquering the Home Front: Radio Biafra in the Nigeria–Biafra War, 1967–1970". War in History. 25 (4): 555–575. doi:10.1177/0968344516682056. S2CID 159866378.

- Stremlau, John J. (2015). The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, 1967–1970. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400871285.

- Venter, Al J. (2016). Biafra's War 1967–1970 : A Tribal Conflict in Nigeria That Left a Million Dead. Helion & Company. ISBN 9781910294697.